Flashes of War at the US Air Force Academy (part 1)

I spoke briefly about flash fiction as a form, quoting Charles Baxter who once wrote that “the novel can win you by points but flash fiction has to win you by TKO.” I described flash a precise exploration of an intimate moment in time, typically involving a situation that outsizes the character. In my stories, that situation is the wars, but it doesn’t always have to be so large. A mother grounding her teenage daughter for a month presents a situation that outsizes the character (of the daughter) and likewise a perfect set-up to write a flash focused on that daughter’s reaction to her circumstances. I also described flash as leaning heavily on that reaction; it’s the reaction that gives our characters nuance, even in a story that’s just 1-3 pages. Reaction, when handled precisely, can reveal that the truth (of our desires, of our predicaments, of our failures, of our potential) is in the immediate details of our lives. That’s why flash doesn’t have to “go big” and build monumental settings or epic character arcs and plots. It can stick to the small–indeed, bully the reader with the small–and in so doing, evoke the grandiose.

In order to explain “why I write about war” or “how I wrote what I did,” two questions I wanted to answer before they were even posed, I paraphrased the epilogue of my book by explaining my interest in language. I showed a brief video I’d made, “Where Research Meets Imagination,” and talked about parallel imagery, imagery as gateway, and using researched language and imagery to bring myself to a moment of disconnect. In short, I explained that my process for writing the book became a matter of researching my way toward a moment of disconnect–a moment where I felt speechless, a writer without words–which then prompted me to imagine exactly the right words and scenarios that would enable me to write a story I could believe in.

The questions that came over the course of the next 40 minutes were smart, open, and thoughtful. The fact that I was sitting in a room full of PhD’s, many of whom were also high-ranking officers, was not lost on me. Indeed, I confessed that I hadn’t taken a literature course since my senior year of high school; I found the English Department at my undergraduate school profoundly intimidating. I know that the USAFA’s faculty questions prompted me to talk about doing purposeful work in life. I know I discussed the limitations of discipline (more on this tomorrow). I know there was an inquiry about the people’s army and the role of the political on the spectrum of research and the imagination. Others wanted to know about why I felt it was important to get the facts right, even in fiction. We likewise talked about the different “brain” it takes to write flash versus writing a novel. But what I want to talk about in this post is the very first question that came at me, or at least, the very first question that got my heart thrumming: “Did soldiers ever get angry at you for writing these stories?”

This question has come at me, and many other civilian war lit authors, in so many different forms, that you’d think I’d have my response down pat. But here’s the thing, and I’ll be frank here: It’s a question that hints at the endless debate about authority and authorization in fiction, and that debate tires me. The debate also frustrates me, because it has a way of making me feel suddenly very distant from most humans and therefore very isolated. Let me try to explain…

In anticipation of this moment, I’d leaned heavily in the war lit friends I’ve made over the last 2 1/2 years. Fine folks like Matthew Hefti, Colin Halloran, Emily Graay Tedrow, Jerri Bell, David P. Ervin, Peter Gordon, Ron Capps, Peter Molin, Kayla Williams, Charlie Sherpa, Jay Moad, and Roxana Robinson–all of whom have helped me in one way or another by sharing their thoughts on this topic along the way. I also re-read Roxana’s fine essay for The New York Times, titled “The Right to Write.” And then I did a few deep breathing exercises, because, honestly, when I have to talk about authority in fiction it makes me feel like the world has failed to value the imagination, and a world without the imagination is a world that is beyond stagnant; it’s a world not worth living for.

Maybe that’s hypersensitive, but that’s the place I go–in my mind and in my heart–when I have to hold the torch and start defending the imagination again, because somehow we’ve forgotten its power, indeed, it’s necessity–not only in great writing, but in the survival of our species. (To be clear: The person who asked me this question, in fact, knows full well about the significance of the imagination; his intent was literal–he wanted to know if I’d run into other people who did not understand the imagination and therefore got angry with me, though that’s not how he phrased his question. I answered his question [No, no one got angry, not to my face] and then proceeded to talk about authority in fiction, because that, of course, was the underlying issue at hand.)

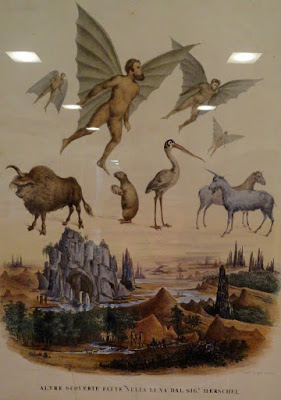

How did we get to this place as a nation? Have we always been so literal, so uncertain about something we can’t hold or touch? When did discipline trump the imagination? When did the imagination take a back seat in classrooms, in teacher trainings, in tactical military training? What is it, precisely, that we are so truly terrified of–our own minds, our own capabilities? The imagination isn’t something to fear; life without it, indeed, a nation or a military run by anyone without it, is damn near the scariest thing I can call to mind. Just yesterday, I saw a 600 year old book in a glass case in the Academy’s special collection room. The book details Alexander the Great’s “dream set up” for warfare, in which he’d have a high, scaffold-like structure with large birds (which a soldier could ride upon) posted at each corner for overseeing battles. That’s the imagination. This room also had early sketches of humankind’s fascination with flight, further evidence of dreamers and of the mind at its creative best. The [ranks] who showed me this room had only been in it twice during their 4 years at the academy: once on their tour of the academy, and once by chance (with me, in that moment). They were too busy, they said, to explore a special collection such as this one. I have no doubt they were too busy–they’re all working their tails off here–but what if they had been invited to dream for a little while in that room, as part of their curriculum? What if…

|

| From the USAF Academy’s aeronautical history collection. |

Maybe we do still imagine with our military might. Someone schemed of “man bats” a century ago. Someone likewise schemed of un-manned planes. Now we have drones. Surely that’s the imagination at work, you might say, but where’s our moral compass that goes along with it? I’m not sure the use of drones is fueled by genuine inquiry–that is, without the intent to indoctrinate or appropriate (or destroy). I don’t know…I just don’t know, which is why this line of thinking can very suddenly make me to go a dark place and why I didn’t say a single word of that previous paragraph in my presentation to the faculty.

Back to the task at hand, in that room, with 35 insanely bright minds waiting on me: I explained that anyone can write anything they want, so long as they have strong writing skills, a willingness to research, effective empathy, and a genuine imagination. I told them I believe that experience isn’t the only teacher and that curiosity goes a long way toward genuine inquiry–which is to say, research infused with a sense of discovery, rather than an agenda to indoctrinate or appropriate. Finally, I expressed that coming at literature from the question of authority was, in fact, to come at it all wrong. Writing, I told them, can have a lot in common with serving your country–both require empathy, integrity, skill, and…yes…the imagination (the ability to think outside the box). At the end of the day, nobody owns the copyright on these skills. Nobody.

How this relates to being a leader in the United States Air Force is something I’ll talk about later today, with the cadets. With a little more gusto, I’ll talk about that dark place, too, and maybe see where the conversation can take us. Stay tuned…