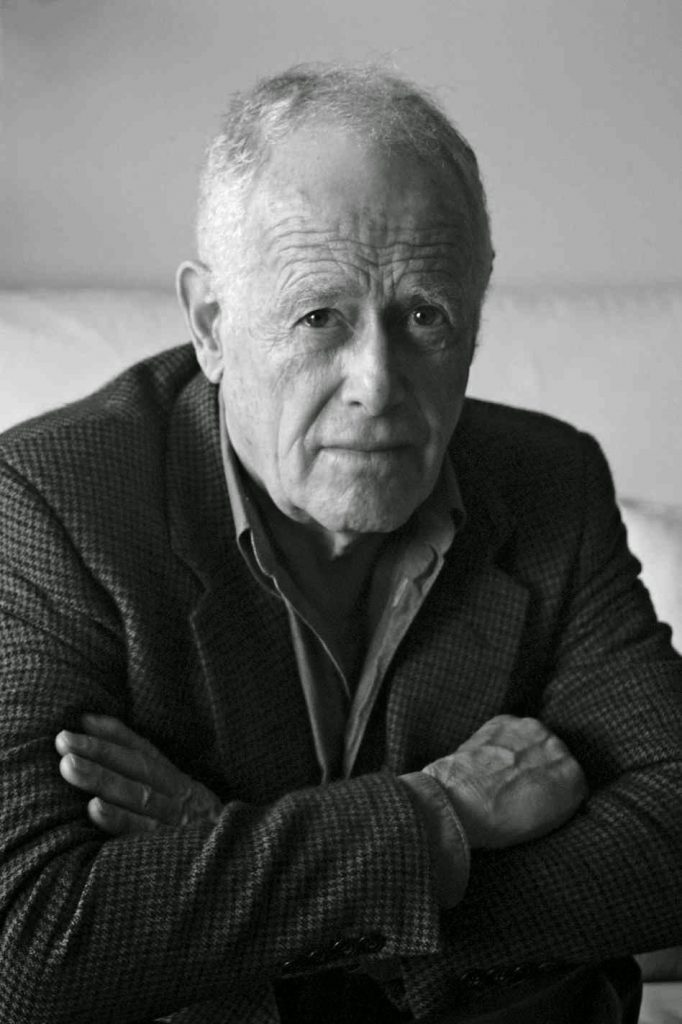

James Salter on Knowledge & Observation

“Big name” authors brought into festivals don’t always make themselves visible or available to the public. In fact, I’ve rarely been at one (or participated in one) where the keynote speaker appears much before or after his/her main event. That’s understandable–they’re not getting compensated for that time and they usually have other things to do. Understandable as it may be, I suspect this fact is sometimes still a little disappointing to festival attendees and participants alike.

“Big name” authors brought into festivals don’t always make themselves visible or available to the public. In fact, I’ve rarely been at one (or participated in one) where the keynote speaker appears much before or after his/her main event. That’s understandable–they’re not getting compensated for that time and they usually have other things to do. Understandable as it may be, I suspect this fact is sometimes still a little disappointing to festival attendees and participants alike.

Ellusiveness was not the modus operandi of this year’s F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Festival’s big name, however, which meant attendees and participating authors alike had ready access to James Salter. At Friday night’s kick-off event, featuring 4 veteran authors and myself, James Salter sat in the front row. Exchanging a few words after the reading, he slipped his 80+-year-old hand into mind and looked at me. “I could stand to read more of your work,” he smiled. “Impressive.”

Did I blush? I must have, though I blush more now to admit that I’m not scholar of Salter’s work. Brushing up on his background a bit over the course of the weekend, his compliment took on greater significance and I felt humbled, honored. Later, during his craft talk and “master class” at the festival, I was able to slip in a question. I asked James Salter how his imagination works. This is a question I always try to be able to answer for myself, as a fiction writer writing far from the realm of anything I’ve personally experienced, and so I’m always eager to hear how others address this topic as well.

I learned two things from James’ answer: First, he, too, describes imagination as that thing we employ when we don’t know the answer, or don’t know what comes next. For me, it’s the gateway (or perhaps the invitation) to write my way toward something I can believe in, toward a truth that feels authentic. To James, it’s sometimes a clue that he needs to rely on other tools–the tools of his life experience–instead, or perhaps, more. When he spoke, James also used the word “invention,” which I thought was particularly thought-provoking. He described having to imagine/invent information or moments in a novel in order to bring an idea to completion. But–and here’s the second thing I learned–for an author such as as himself, imagination is secondary to “knowledge and observation.” Knowledge and observation, James said, guide him through nearly everything he lives and writes. Because his fiction doesn’t stray too terribly far from what he’s experienced, that makes sense. But I had never thought of placing these three things–knowledge, observation, and imagination–on a spectrum before. I’ve lectured about where research meets imagination, but James’ answer gave me more terms to work with and consider, adding good old fashioned “observation” back into the mix.

Observation, of course, is such a close friend to every writer that it’s easy to forget it’s a skill that comes in hand most especially during those long, silent, solo hours at the desk. For a writer, observation is always there, the logbook pages always filling, the “recorder” always ready to save impressions, and the eye always keen to those things others often miss. For most writers, I’d argue, observation is second nature; so essential to who we are, we don’t even know how to separate ourselves from it.

Which is perhaps why, when I talk about research and imagination–my two main tools–I’ve forgotten to mention observation altogether. It’s worth bringing this back into my consciousness, though, as my “war stories” are really just “people stories.” And what do I observe day after day after day? People. How people behave is the gateway to the shared predicaments of the human heart, which–in my opinion–is a topic any story or novel must address, whether sideways or head-on.